You can't always dance like no one's watching

Plus, some bad art.

GM. Today is just one of those days when I feel like eating a pain au chocolat would save my life. Anyway, let’s get on to the news.

Banksy is back. And their art is still bad. The anonymous British street artist has unveiled (at least) four new artworks this week, all of animal silhouettes. There’s a mountain goat, two elephants, three monkeys, and a lone wolf. What’s next, two turtle doves? Give me a break.

Band and orchestra kids are winning. New research published in the journal PLOS One found the benefits that children gain from playing in classical music ensembles, including enhanced critical thinking, self-awareness, confidence, discipline, time management, and team-building. And yet, according to The National Assessment of Educational Programs in the Arts, arts education in schools has been on the decline since the late ’90s, and since 2010, it estimates that a majority of fine arts departments in public schools have seen budget cuts. Tomato tomato tomato!!!

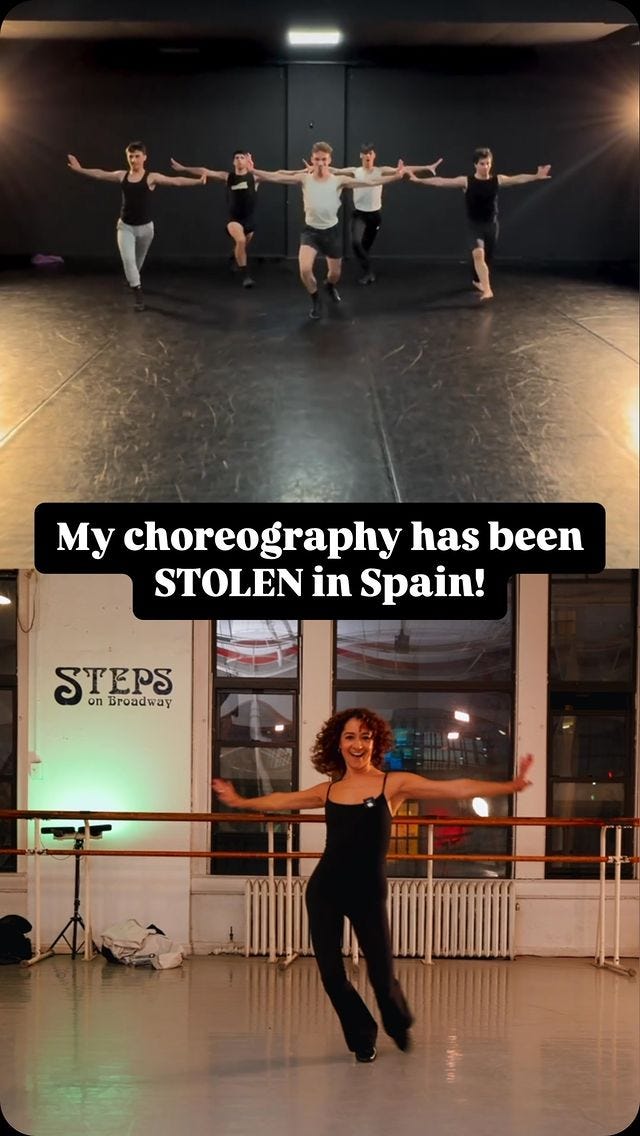

Can you plagiarize a dance? Short answer: Yes. And that’s exactly what happened when a Madrid dance studio began teaching choreography by Steps on Broadway instructor Courtney Ortiz. In July, Ortiz posted a video on Instagram calling out the studio, which has effectively ceased and desisted. But this isn’t an unusual problem.

As Playbill reports, it is increasingly hard for choreographers to protect their work—and many aren’t seeking additional monetary gain from doing so, but rather a standard of ethics. TikTok, for its part, has really muddled this issue, and many professional choreographers actually are not very happy when their dances are performed on the app en masse. We’ve also seen the erasure of upstart choreographers. Think of how then-14-year-old Jalaiah Harmon created the TikTok-famous “Rengade” dance and received little credit until eventually, months later, a whole media cycle talked about how she wasn’t getting credit for it. (My favorite response was Sufjan Stevens’s lovely decision to cast Jalaiah as the star and choreographer of his “Video Game” music video).

There have been some improvements on this front. See how commenters have responded to NYC actor Kelley Heyer’s video of her creation, a viral dance to Charli xcx’s “Apple.” (Jalaiah, for her part, now has more than 3 million TikTok followers, too).

Unionized choreographers have protections against unauthorized reproductions of their work, and big-name choreographers—living and deceased—have successfully copyrighted their work, though Playbill notes that this process is long, expensive, and difficult to enforce when a work is illegally reproduced overseas.

The Copyright Act of 1976, which went into effect in 1978, made choreography a protectable form of expression. And legal battles have arisen regarding the rights of dances; in 2002, for instance, the Martha Graham Center won a tough battle against Ron Protas, the former associate director of the Center and Graham’s heir. The court ruled that because Graham created her dances as an employee of the Center, she therefore could not will them to an individual. The George Balanchine Trust, established in 1987, is considered the gold standard of choreography protection, as it handles the licensing of Balanchine’s ~75 ballets—though there are accounts that while he was alive, Balanchine had a pretty laissez-faire approach to who he allowed to perform his work.

As with books, copyright-protected dances become public domain 70 years after the death of their creator. This is why a lot of classical ballets can freely draw from iconic, long-deceased choreographers like Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov. And while dance is passed down through oral—or performed—tradition, technology is a key tool in copyright protecting it. Balanchine, for instance, copyrighted his version of The Nutcracker (which has some influences from Ivanov) by submitting a tape of a dress rehearsal to the U.S. Copyright Office in 1981, according to the Fordham Intellectual Property, Media & Entertainment Law Journal. You can dance how you want when no one’s watching—but it might not always be legal to freely perform the choreography of the greats.

Harvard sticks with a Sackler. The university has declined to remove Arthur M. Sackler’s name from one of its art museums, in spite of student protests. The committee that made this decision found the argument insubstantial, especially since Arthur Sackler died in 1987, before Purdue Pharma—the company he started with his two brothers—developed and released OxyContin in 1995. Students argued that marketing tactics Arthur developed helped later fuel the opioid epidemic, although the man played no literal role in the development and sale of the addictive pharmaceutical.

The photographer Nan Goldin, who survived an addiction to OxyContin and a nearly fatal fentanyl overdose, founded the activist group P.A.I.N (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) in 2017 and successfully lobbied for several arts institutions to remove the Sackler name from their walls, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Some Sacklers remain: the Brooklyn Museum’s Elizabeth A. Sackler Center, for instance, remains named for Arthur’s daughter.

Uno reverse. Here’s an update on the book ban front: Last fall, Fresno, California County Supervisor Steve Brandau created a citizen review committee, which could require children to get parental permission to check out public library books deemed to have “sexual references” and “gender-identity content.” To be clear, this is a crackdown of, and a sexualization of, children’s books with LGBTQ+ characters. But this may—for once—be stopped. AB 1825: California Freedom to Read Act, which is expected to pass in the state legislature by August 31, would ban such committees…in effect, banning book bans.

This may be controversial but…artistic gymnastics would benefit from more of an appreciation of dance, argues the New York Times’s Laura Cappelle. Although choreography and artistry are considered a part of a gymnast’s score in the Olympics, dance often feels like an “afterthought,” she writes. This is no discredit at all to the gymnasts themselves: The timing restrictions of floor routines and even the filming of the routines allow little room for choreography to breathe or be appreciated.

I’m inclined to agree—and I especially love seeing when a gymnast, like Brazil’s Rebeca Andrade, fluidly moves from dance to tumbling pass or when Jordan Chiles executes the jazzy interludes of her Beyoncé floor routine with personality. I find Sunisa Lee so enjoyable to watch because of the way she completes her lyrical choreography, fully stretching her limbs, and because of her stunning leaps and pointed feet. “If gymnastics really values artistry and wants the audience to focus on it, options exist, from limiting tumbling passes to allowing longer routines, or awarding virtuosity bonuses to the best performers,” Cappelle writes. “That would involve thinking of each floor routine as a miniature choreographic work: an organic whole that deserves to be enjoyed fully by every audience, live or on TV.”

Until then, we can always watch rhythmic gymnastics, too

How can we teach philosophy in 2024? According to the University of Miami, through VR. Doctoral student Matthew Watts—who was recognized this year by the American Philosophical Association for his unique teaching strategy—uses virtual reality headsets to help illustrate philosophical concepts and engage students. “Modern philosophy was born in virtual reality—in the form of a series of thought experiments devised by René Descartes,” department chair Mark Rowlands says. “Matthew is carrying on a venerable tradition of thought but doing so using a cutting-edge technology that extends its possibilities in a way Descartes could scarcely have imagined.”

I blink; therefore, I am, perhaps? ▲

I guess the trolley problem in VR hits different