Looking into the mirror

Confronting the double in two new works of contemporary dance.

The following is a review-slash-analysis of two new works of dance I saw in April. Maybe you will enjoy this sort of thing?

It is a dancer’s job to continually confront the self, regarding their mirrored reflection in technique classes and rehearsals. It is this practice, maintained for hours over decades of training, that affords them the ability to perform to crowds in the hundreds or thousands at a height of vulnerability that might be more easily expressed in solitude. Yet, in two world premieres that debuted this month, dancers Xin Ying, of the Martha Graham Dance Company, and Sara Mearns, in her artist’s residency at New York City Center, take to the stage in apparent disregard for the hordes which watch them.

The dilemmas they untangle in these works, after all, are personal and involve a confrontation with a double to ease into a final beat of self-actualization. It is clear, from my balcony seat at each performance, that what’s happening on stage is not done for my benefit as an audience member; it is simply something they need to do.

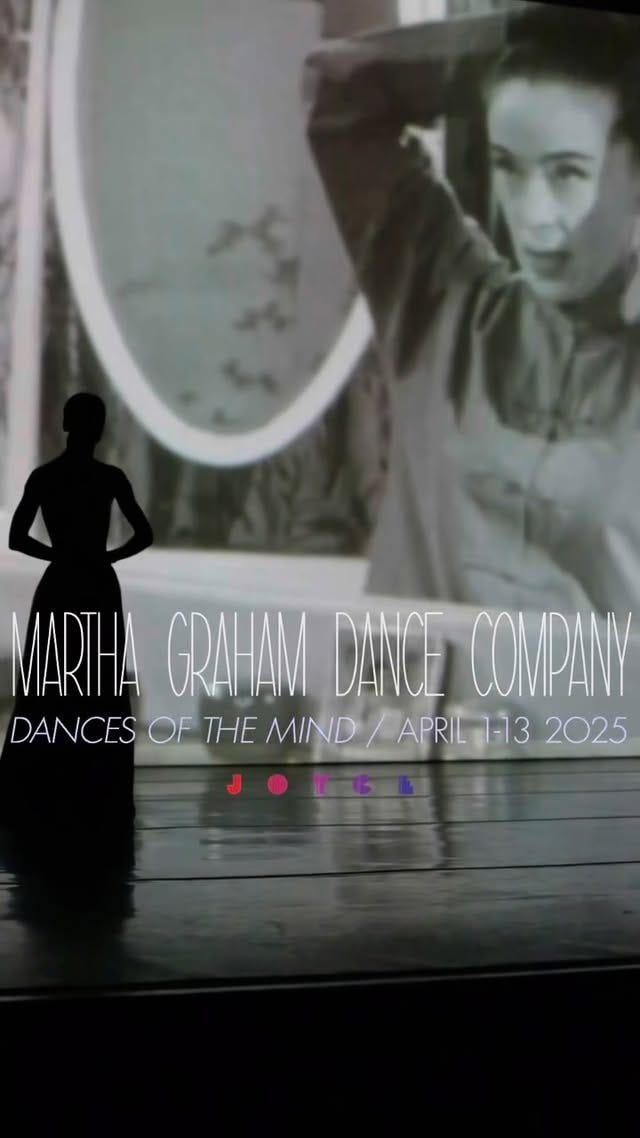

Ying’s solo, Letter to Nobody, which she choreographed with collaborator Mimi Yin, could technically be considered a duet. Projected onto a screen behind her is Martha Graham, the founder of the company, who died in 1991. Dressed in a long, ruffled dress, Graham performs her solo, Letter to the World, inspired by the Emily Dickinson poem of the same name. The expansive sweep of her skirt and upward rotation of her wrists — in their precision and clarity — are emblematic of the dancer’s signature style. With her back to the audience, Ying is dwarfed by Graham’s almost spectral image, which pops in and out of view, appearing in one spot and departing from another.

When Graham, on screen, is joined with other dancers, Ying’s movement expands in its urgency. She moves across the stage on her knees in restrained, quick steps forward. She whips her torso around on its axis, in repeated 360-degree rotations, an outstretched leg fanning forward her ankle-length skirt as if her body itself were the flag of a color guard performer. Her movement is insistent and yearning. It is impossible to catch up with Graham, whose appearance now becomes less predictable. A voice — Graham’s — quotes another poem of Dickinson’s, this one the source material for Ying’s work: “I’m Nobody! Who are you? / Are you – Nobody – too?” Shortly thereafter, Ying herself repeats the verse, turning to address the audience directly. She has brought us in.

Much of the movement in Letter to Nobody evokes Graham’s original Letter to the World, though the tone of Ying’s piece is decidedly more alien. The controlled contractions found in so much of Graham’s choreography — particularly in Clytemnestra, which started the evening’s program — lend the dancer a feeling of anguish, one that culminates in an indelible final image. On screen, Graham, sitting at a dressing table, speaks directly to the camera. It is an archival clip from the 1957 short film A Dancer’s World. With her hair piled into a voluminous bun, Graham explains how a dancer must embody the character she is trying to portray. But what’s happening on screen is at first deceptive, subtle enough for an audience member to question if they’re seeing correctly before trusting what’s before their own eyes. Ying’s face has been transposed onto Graham’s, as Graham’s voice says: “There comes a moment when she looks at you in the mirror, and you realize that she's looking at you and recognizing you as herself.”

During this sequence, Ying, onstage, has removed her skirt and faces the audience in her leotard. The lights begin to dim as she collapses gracefully forward, sliding her legs out to bring her torso, held parallel to the stage, lower and lower. Her arms stretch out like a powerful yet frozen wingspan. Graham’s own visage returns, and the stage turns to black. The audience emits a gutteral sigh.

The virtuosic Ying, who has performed with the Martha Graham Dance company since 2011, is an appropriate figure to come, in a sense, face-to-face with Graham. By making Graham her double, Ying expresses an anxiety about carrying forward the artist’s legacy, and as Graham’s face replaces Ying’s on screen, it becomes clear how the dancer understands her role. She cannot subsume this double; she embraces the identity of Nobody perhaps because it is in this a negation of the ego that she can best carry forward the legacy of her foremother.

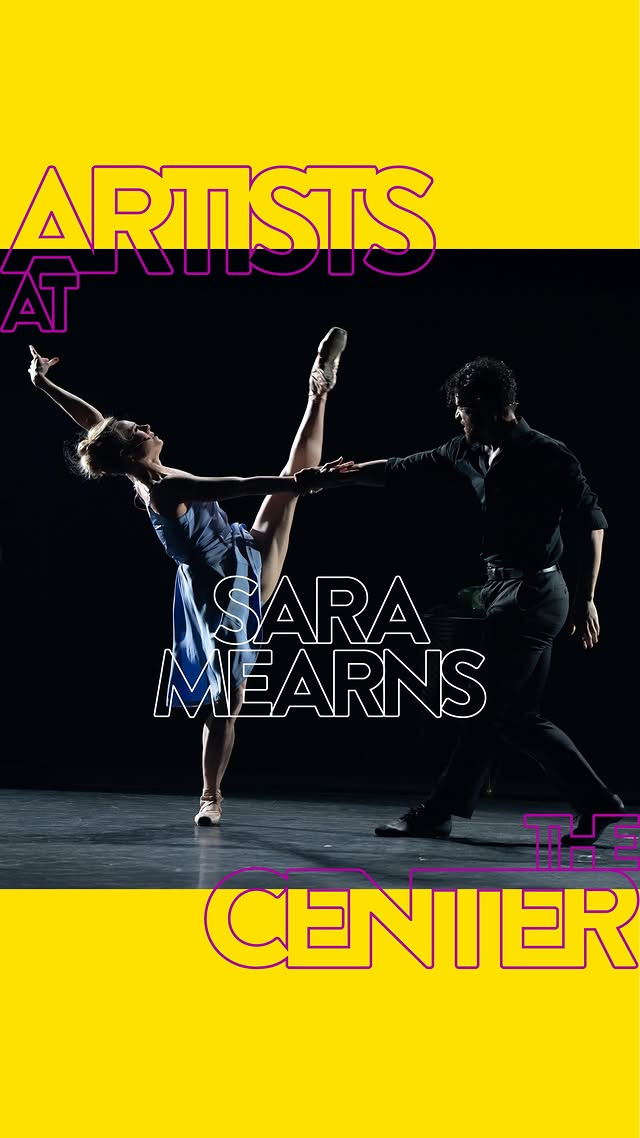

In Don’t Go Home, a dance theater piece conceptualized by Mearns, Guillaume Côté, and Jonathan Young (with Côté directing and choreographing and Young writing the piece), the New York City Ballet principal dancer plays the autofictional role of “Sara.” She walks onto the stage, which is dressed but not lit, and lies on her back, placing her legs in the air. Intermittently, she shakes them, loosening her muscles. From above comes the voice of a director, “Hey Sara?” he asks. Did she realize they were starting?

This opening scene, during which Mearns speaks with the disembodied voice, starts the piece with humor. It’s all a bit meta. But as the story progresses and we see “Sara” auditioning for the role of “Claire” — a dancer in a movie whose life is suspiciously similar to her own — it takes on a darker and decidedly self-reproachful tone. The director is accommodating of this apparent audition but is dismissive at best and mocking at worst. Does she know, he asks, that Claire is supposed to be a really good dancer?

The program reveals that Côté devised his script after reading two years’ worth of Mearns’s private notes — “thoughts that otherwise shouldn’t see the light of day.” On her own Instagram, Mearns has been open about struggles with depression and injuries; in December, she shared that she got permanent hearing aids after a decade of worsening hearing loss. It is not necessary to know Mearns’s personal story to understand or appreciate Don’t Go Home, but the context does add to its effect.

Throughout the piece, “Claire” exists as a double who shares Mearns’s body; it is not always clear, intentionally, when she is playing Sara and when she is playing Claire. The performance climaxes, however, when Sara comes to the realization that she understands Claire intimately. This role, she feels, needs to be hers. She moves through the set pieces that simulate her apartment — she told the director that to better understand Claire, she moved the furniture in her space to exactly replicate that of the character. When she opens the door, another double stands before her.

Dancer Anna Greenberg, whose role in this work is literally noted as “The Double,” is dressed exactly like Mearns in pointe shoes, a blue ballet dress, and coiffed blonde hair. They dance slowly, face to face, creating a mirror effect. Electronic guitar and percussion intensify and the lights periodically flicker on and off to show the dancers Greenberg, Mearns, and Gilbert Bolden III — who plays Sara’s boyfriend Mark, Claire’s boyfriend Adam, and his autofictional self, Gilbert — in various positions. They move through a mix of sweeping, athletic partnering and big, outward extensions for which Mearns is so well-known. By the end of the piece, Sara understands how to embody Claire. “It’s not this,” she says, moving through awkward sequences with Bolden which leave them repeatedly binded or caught in their movements. “It’s this,” she says, finally, pressing a hand to her heart.

The double, or doppelgänger is not unfamiliar in the world of classical ballet. It’s found most famously in Swan Lake, as the black swan Odile sabotages the white swan Odette, but it also appears in Coppélia, wherein the dim Franz falls in love with a doll who he believes to be real, sparking the jealousy of his fiancée Swanhilda and leading her, in a prank, to assume the identity of the doll. One could also argue that the Nutcracker prince, in many versions of The Nutcracker, is himself a double, existing as the nephew of beloved Uncle Drosselmeyer in one world and royalty in the Land of Sweets. These doubles push forward the plots of their ballets, acting as instigators to either tragedy, trick, or treat.

The doubles in Ying and Mearns’s contemporary works more explicitly represent an idealized form with which the dancers attempt to meld. In each case, however, the dancers remain their split and separate selves. In a moment of strong social alienation — due, perhaps, to the ever-present pressures of social media, the rapidly dwindling largescale public and private support for the arts, and growing authoritarian pressures — the individual alone may feel inappropriately fortified for survival. But in these dances, personal discipline overrides determinism. All they have is their selves.

In A Dancer’s World, Graham proclaims that a dancer’s only competition is between themselves and the individual they know they can become. “It is a creative process,” she says. “It is out of that handling of the material of the self that you are able to hold the stage in the full maturity and power which that magical place demands.” ▲