Back to school

Plus, some picks for your TBR.

Happy Sunday. I hope you are enjoying the season that will soon officially be fall. September always feels like a fresher start to me than January. I’ve reorganized my drawers and have ambitions to clean out my closet even more than I already have, and my big goal for the month is to finally finish 2666.

In the meantime, let’s chat.

What is the purpose of the university? I’ve been thinking a lot about Erik Baker’s most recent story for Harper’s, in which he interrogates the current state of—and the prospective future—of college in American society. Rumors of the death of the English major have been par for the course for the past decade, if not longer, but what I find most compelling about Baker’s analysis is that he’s not ultimately concerned about crowning a victor in the STEM vs. humanities debate. And indeed, he points out that this very debate has long, historic legs stretching back to the early 20th century. The point less often extrapolated is the fact that STEM degrees, too, do not necessarily procure their alleged promise to society.

The humanities hold little promise for financial gain. STEM makes a more enticing offer in that regard, but technical innovation may not necessarily be the answer either. “Those who do get rich these days, regardless of their educational background, do so largely by owning appreciating assets such as stocks and real estate,” Baker writes. “Even corporate executives acquire the lion’s share of their wealth through capital gains on stock options rather than through their salaries.” Non-technical employees at Nvidia must surely concede.

In this case, naturally, students view college as “an exchange of time and tuition dollars for credentials and social connections more than a site of valuable learning,” as Baker describes. So what’s the point of learning, anyway?

Shifting political attitudes toward higher education—with less than 20 percent of Republicans expressing “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the institution compared to 59 percent of Democrats, Baker notes—have been shaped by rising and prohibitive costs of entry, and of course discourse, over the past year in particular, over the freedom of political expression and university endowment investments. Aside from these matters, there is also, seemingly, a growing skepticism about the value of learning for learning’s sake.

In a piece for the New York Review of Books last year, Marilynne Robinson wrote that critics of education suggest that its traditional form does “not produce workers suited to the present or the future economy.” Of course, “no one could have foreseen 20 years ago the economy we have now, and no one is quite certain what will happen in the next five years,” she adds, “But there is a quite aggressive push to conform, to narrow, students’ skills, priorities, and expectations to meet the demands of the dreary future anticipated by these supposed realists, which will probably eventuate only to the extent that we embrace their ‘reforms.’”

There is a reason why reading, say, Ovid, seemingly transmuted a greater value to students in the past than it does today. The study of the humanities, especially in antediluvian university life, “prepared young American aristocrats to rule by equipping them with discipline and character,” Baker says, as the expansion of American capitalism necessitated a smart reinvestment of profit which “required a firm sense of duty and purpose, to ward against the temptation to squander fortunes on idle luxuries.” The Western canon, ostensibly, developed that sense in wealthy white men.

If we stretch even farther back in time, however, we find a far more generous explanation for the purpose of education, as Robinson references in a more recent NYRB piece:

American higher education is of the kind historically called liberal, that is, suited to free people, intended to make them independent thinkers and capable citizens. “Liberal” comes from the Latin word liber, meaning “free.” Aristotle, a theorist on this subject of incalculable influence until recently, considered education a natural human pleasure, essential to the perfecting of the self, which he says it is in our nature to desire. Obviously when he taught there was no thought of economic utility that would subordinate learning to the purposes of others, to the detriment of individual pleasure or self-perfection. Training in athletics, music, then philosophy were to be valued because they are liberating.

This kind of education, she adds, has been associated with elitism, which is, again, a blight caused by the exorbitant cost of a college education; student deferments during the Vietnam War, she adds, also played a role in growing skepticism of this system. “This hostility,” Robinson writes, “traces back to the social polarization that associated [universities] with privilege and immunity rather than with the humane value of learning for its own sake.”

Where does this leave us? I’ll admit I’m not entirely sure. The cost of a college education—paired with the end of affirmative action—has increased the height of ivy-covered gates. As Robinson says, “education is undermined by the hollow elitism that allows the wealthy to work the system, making the children of wealth look interesting to selective institutions, as they would not without the ministrations of coaches and, in effect, ghostwriters, to put the bloom of promise on their young cheeks.”

All the while, students who do get the chance to pursue higher education may be able to rise financially, but Baker notes that this is no guarantee, and after all, “an economy in which the best way to get rich is to be born rich is one in which the value proposition of a college education is hazy no matter what you intend to study.” Why stay in school if Peter Thiel will give you $100k to drop out and start a company instead? There is even little understood advantage for would-be aristocrats to engage in the liberal arts as their early 20th-century forebears had. “[I]t is not clear that the gentry of the asset economy will feel the same need for moral cultivation that possessed their nineteenth-century predecessors,” Baker writes.

I worry about an educational system in which curiosity and critical thinking are not prioritized or valued. I worry about younger generations that see little to gain from engaging with historical perspectives or theory. And yet, I know that it is a privilege to divorce one’s education from one’s financial future; I knew that when, more than a decade ago, I prioritized writing bad listicles for embarrassingly low pay over engaging more deeply and meaningfully with my course reading. It is only now, with hindsight and a more mature perspective, that I yearn to get back to the classroom, simply to read and learn and soak up the expertise of my perspectives. I wonder now if an equitable educational system that teaches its students to think and really, earnestly engage with the world around them—above all else—can ever exist.

Because at the other end of a college degree is a career. And prioritizing financial mobility—for those without a trust fund, some other financial padding, or complete luck at finding a rare, well-paid passion job—means you likely won’t have a real need to do the difficult work of academically engaging with the liberal arts, because it will play no role in your corporate recruiting outcomes. Is it overly optimistic to assume students en masse will engage in learning in spite of that? Or does the rapidly expanding usage of ChatGPT in academic settings answer that question for us?

At the very least, I will assume, there could be some level of self-aware sardonicism regarding the utility of one’s education; I myself tweeted, in 2016 during my final semester of college: “today my canterbury tales professor complimented my recitation of middle english @employers employ me I have valuable skills.” I have always valued academics, but I’ll freely admit that my college decision was largely driven by the need I felt for my career to intern at magazines throughout my undergrad education.

There are, admittedly, students who view their early career as a brief layover before they do the work of putting their education into action. “Nowadays, English concentrators often say they’re going into finance or management consulting for a couple of years before writing their novel,” James Wood, Harvard professor of the practice of literary criticism, told the NYT.

Mihir Desai, who teaches at both Harvard Business School and Harvard Law, has long expressed skepticism about the ability of students to change course in that way: “What it gets wrong is, you spend 15 years at the hedge fund, you’re going to be a different person. You don’t just go work and make a lot of money, you go work and you become a different person.”

The dream to learn, just for the sake of it, is a fantasy only afforded to those most privileged members of society. It has been this way for a long time. On May 12, 1780, John Adams wrote to his wife, Abigail:

I could fill Volumes with Descriptions of Temples and Palaces, Paintings, Sculptures, Tapestry, Porcelaine, &c. &c. &c. -- if I could have time. But I could not do this without neglecting my duty. The Science of Government it is my Duty to study, more than all other

StudiesSciences: the Art of Legislation and Administration and Negotiation, ought to take Place, indeed to exclude in a manner all other Arts. I must study Politicks and War that my sons may have liberty to studyPainting and PoetryMathematicks and Philosophy. My sons ought to study Mathematicks and Philosophy, Geography, natural History, Naval Architecture, navigation, Commerce and Agriculture, in order to give their Children a right to study Painting, Poetry, Musick, Architecture, Statuary, Tapestry and Porcelaine.

I believe, perhaps naively still, in a world where it doesn’t have to be this way.

TBR. The National Book Awards has released its longlists for fiction, nonfiction, poetry, translated literature, and young people’s literature. More than half of those listed for those first two categories are published by Penguin Random House, Maris Kreizman noted on Twitter. Seems not great for the industry at large. Personally…I will be drawing my attention to the literature in translation. Finalists for the awards are announced October 1.

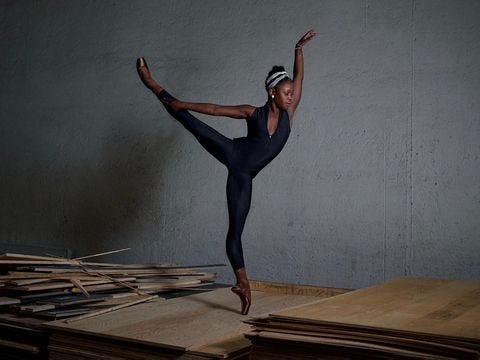

The ballet world loses a bright star. Michaela Mabinty DePrince, a ballerina who rose to acclaim after her appearance in the 2011 documentary First Position tragically passed away on Tuesday at the age of 29. Mabinty was born in Sierra Leone during its nearly 11-year Civil War and adopted at age 4 by an American couple. She trained on scholarship at American Ballet Theatre’s Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School and performed as a principal at the Dance Theater of Harlem and a soloist at the Dutch National Ballet and Boston Ballet. Her memoir, Taking Flight: From War Orphan to Star Ballerina, was published in 2014.

“Michaela Mabinty managed to achieve one of the rarest things in the ballet world,” wrote English National Ballet former artistic director Tamara Rojo, who worked with her in 2017 on a production of Giselle. “She was a dancer who transcended the industry and reached the hearts of a public beyond our artform.”

Better together. Juilliard has received a $15 million gift to support its Creative Enterprise program, which aims to unique the school’s various disciplines through collaborative projects, such as its fully remote production of Bolero in April 2020.

Also, speaking of Bolero, if you live in New York, you have until September 22 to see the Morgan’s excellent exhibit on the Ballet Russes.

Something to discuss with your Hinge date who lives in South Brooklyn. Robert Caro’s The Power Broker—his nearly 1,200 page tome about defining city planner Robert Moses—has turned 50. Caro, 88, is currently working on the last volume of his five-book Lyndon Johnson biography. ▲

Not the power broker 💀